Hull–White model

In financial mathematics, the Hull–White model is a model of future interest rates. In its most generic formulation, it belongs to the class of no-arbitrage models that are able to fit today's term structure of interest rates. It is relatively straightforward to translate the mathematical description of the evolution of future interest rates onto a tree or lattice and so interest rate derivatives such as bermudan swaptions can be valued in the model.

The first Hull–White model was described by John C. Hull and Alan White in 1990. The model is still popular in the market today.

Contents |

The model

One-factor model

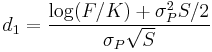

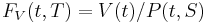

The model is a short-rate model. In general, it has dynamics

There is a degree of ambiguity amongst practitioners about exactly which parameters in the model are time-dependent or what name to apply to the model in each case. The most commonly accepted hierarchy has

- θ constant – the Vasicek model

- θ has t dependence – the Hull-White model

- θ and α also time-dependent – the extended Vasicek model

Two-factor model

The two-factor Hull–White model (Hull 2006:657–658) contains an additional disturbance term whose mean reverts to zero, and is of the form:

Where  has an initial value of 0 and follows the process:

has an initial value of 0 and follows the process:

Analysis of the one-factor model

For the rest of this article we assume only  has t-dependence. Neglecting the stochastic term for a moment, notice that the change in r is negative if r is currently "large" (greater than θ(t)/α) and positive if the current value is small. That is, the stochastic process is a mean-reverting Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process.

has t-dependence. Neglecting the stochastic term for a moment, notice that the change in r is negative if r is currently "large" (greater than θ(t)/α) and positive if the current value is small. That is, the stochastic process is a mean-reverting Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process.

θ is calculated from the initial yield curve describing the current term structure of interest rates. Typically α is left as a user input (for example it may be estimated from historical data). σ is determined via calibration to a set of caplets and swaptions readily tradeable in the market.

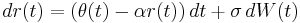

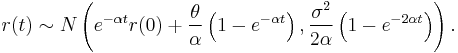

When  ,

,  and

and  are constant, Itô's lemma can be used to prove that

are constant, Itô's lemma can be used to prove that

which has distribution

where  is the normal distribution.

is the normal distribution.

Bond pricing using the Hull–White model

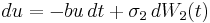

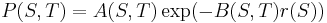

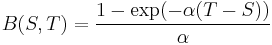

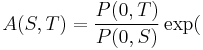

It turns out that the time-S value of the T-maturity discount bond has distribution (note the affine term structure here!)

where

Note that their terminal distribution for P(S,T) is distributed log-normally.

Derivative pricing

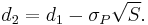

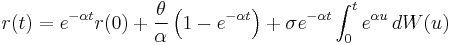

By selecting as numeraire the time-S bond (which corresponds to switching to the S-forward measure), we have from the fundamental theorem of arbitrage-free pricing, the value at time 0 of a derivative which has payoff at time S.

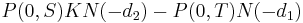

Here,  is the expectation taken with respect to the forward measure. Moreover that standard arbitrage arguments show that the time T forward price

is the expectation taken with respect to the forward measure. Moreover that standard arbitrage arguments show that the time T forward price  for a payoff at time T given by V(T) must satisfy

for a payoff at time T given by V(T) must satisfy  , thus

, thus

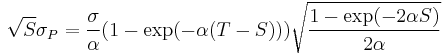

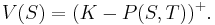

Thus it is possible to value many derivatives V dependent solely on a single bond P(S,T) analytically when working in the Hull–White model. For example in the case of a bond put

Because P(S,T) is lognormally distributed, the general calculation used for Black-Scholes shows that

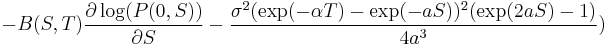

where

and

Thus today's value (with the P(0,S) multiplied back in) is:

Here σP is the standard deviation of the log-normal distribution for P(S,T). A fairly substantial amount of algebra shows that it is related to the original parameters via

Note that this expectation was done in the S-bond measure, whereas we did not specify a measure at all for the original Hull-White process. This does not matter — the volatility is all that matters and is measure-independent.

Because interest rate caps/floors are equivalent to bond puts and calls respectively, the above analysis shows that caps and floors can be priced analytically in the Hull–White model. Jamshidian's trick applies to Hull-White (as today's value of a swaption in HW is a monotonic function of today's short rate). Thus knowing how to price caps is also sufficient for pricing swaptions.

Trees and lattices

However, valuing vanilla instruments such as caps and swaptions is useful primarily for calibration. The real use of the model is to value somewhat more exotic options such as bermudan swaptions on a lattice or other derivatives in a multi-currency context such as Quanto Constant Maturity Swaps, as explained for example in Brigo and Mercurio (2001).

See also

References

Notes

- Hull, John C. (2006). "Interest Rate Derivatives: Models of the Short Rate". Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives (6th ed. ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J: Prentice Hall. pp. 657–658. ISBN 0131499084. OCLC 60321487. LCCN 2005-047692.

Articles

- Damiano Brigo, Fabio Mercurio (2001). Interest Rate Models — Theory and Practice with Smile, Inflation and Credit (2nd ed. 2006 ed.). Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-22149-4.

- John Hull and Alan White, "Using Hull-White interest rate trees," Journal of Derivatives, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Spring 1996), pp 26–36

- John Hull and Alan White, "Numerical procedures for implementing term structure models I," Journal of Derivatives, Fall 1994, pp 7–16

- John Hull and Alan White, "Numerical procedures for implementing term structure models II," Journal of Derivatives, Winter 1994, pp 37–48

- John Hull and Alan White, "The pricing of options on interest rate caps and floors using the Hull–White model" in Advanced Strategies in Financial Risk Management, Chapter 4, pp 59–67.

- John Hull and Alan White, "One factor interest rate models and the valuation of interest rate derivative securities," Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Vol 28, No 2, (June 1993) pp 235–254

- John Hull and Alan White, "Pricing interest-rate derivative securities", The Review of Financial Studies, Vol 3, No. 4 (1990) pp. 573–592

- Eugen Puschkarski, "Implementation of Hull-White´s No-Arbitrage Term Structure Model", Diploma Thesis, Center for Central European Financial Markets

- Letian Wang, Hull-White Model (with detailed numeric example), Fixed Income Quant Group, DTCC

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

![d\,f(r(t)) = \left [\theta(t) %2B u - \alpha(t)\,f(r(t))\right ]dt %2B \sigma_1(t)\, dW_1(t)\!](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7e529b0c23c75078b540bbf462c1f4cb.png)

![V(t) = P(t,S)\mathbb{E}_S[V(S)| \mathcal{F}(t)].\,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f91fd479c61fba3fe17319a842924454.png)

![F_V(t,T) = \mathbb{E}_T[V(T)|\mathcal{F}(t)].\,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3fed3ec3d1bad1c6ed4fb5434f48db06.png)

![{E}_S[(K-P(S,T))^{%2B}] = KN(-d_2) - F(t,S,T)N(d_1)\,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/bdd62b758f9ddab241aae227fce83520.png)